VOLUME 2 / ARTICLE 04 ︎

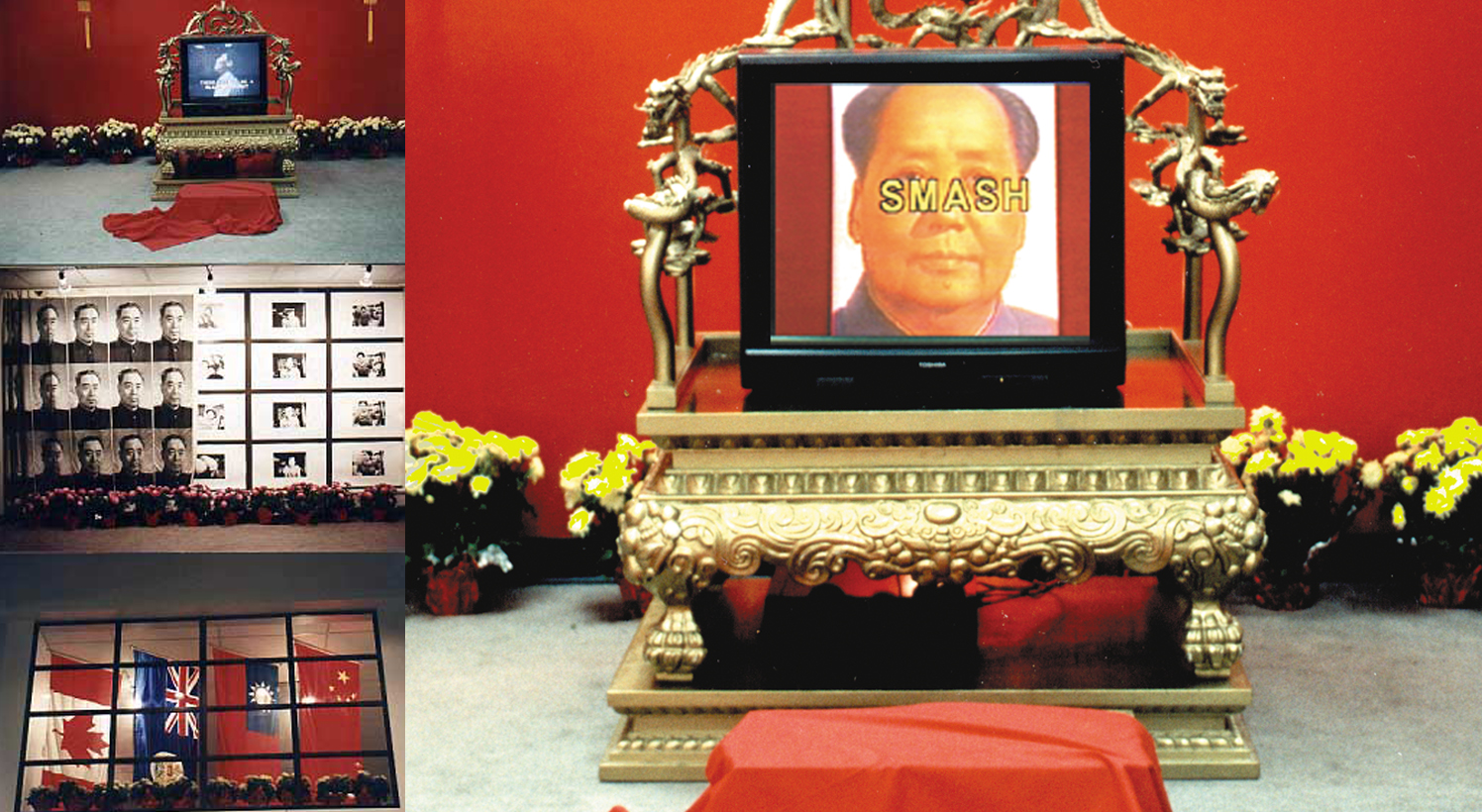

Pictured is Paul Wong’s Ordinary Shadows, Chinese Shade (1988) from the Collection of the National Gallery of Canada and Museum of Modern Art.

MAIN STREET OG, MEDIA ARTS

MASTER: PAUL WONG

MASTER: PAUL WONG

Written by Serene Mitchell

Photos courtesy of Paul Wong

November 202

Photos courtesy of Paul Wong

November 202

Paul Wong, photographed by Serene Mitchell in his studio in Vancouver's Chinatown in October 2020.

Over the last five decades, Vancouver based media artist Paul Wong has worked to tell stories and ask questions within critical spaces and on screens of all sizes. Wong’s work is known for using thought-provoking and shocking images to comment on the intersections of capitalism, sex, death, race, and ancestry. At the forefront of building community within the media art world since its emergence, Wong skillfully wove together a network of artists across the globe, producing a quintessential climate for self-proclaimed art to assert its merit within dominant avant-garde spaces. In the last three years, Wong has brought his expertise to Vancouver’s Chinatown, curating Pride in Chinatown and creating spaces for queer Asian artists in one of Canada’s largest historic urban enclaves. Wong’s works can be found in public collections at the National Gallery of Canada, the Museum of Modern Art (in New York City), the Vancouver Art Gallery, and the Canadian Council Art Bank.

Born in Prince Rupert, British Columbia, in 1954, Wong first picked up a Portapak video camera when he was attending high school at Sir Charles Tupper Secondary. Wong’s experiences growing up with parents who work in separate cities reflect the stories of many children of first-generation immigrants. Wong remembers his family being labeled by people inside and outside of the Chinese community as not conforming to the “model minority myth.” He recalls a particular experience he had in high school that encapsulated this: “I remember getting called into the principal's office. The principal asked me, ‘what’s wrong with you and your siblings? Why don’t you act like the rest of your people?’”

With the onset of Canadian multiculturalism policy in the 1970s, stories like Wong’s, of racialized stereotypes and isolation, are often systematically erased. He had to negotiate and search for places to find belonging: “I did not fit into anyone’s prescribed expectations, from family to outside the family, but also the media.” He notes, “That was the catalyst to find other like-minded outsiders in the school system; in my case, it happened to be an attraction to the smokers, the drinkers, the artists. It was a natural place that allowed for creativity, queerness, and otherness. Here I could be [myself] and be okay.”

In the 1970s, Wong and his friends Kenneth Fletcher, Deborah Fong, Carol Hackett, Marlene MacGregor, Annastacia McDonald, Charles Rea, and Jeanette Reinhardt formed the Mainstreeters. They were a young art collective based around Vancouver’s Main Street, pushing back on the commodified and professionalized art world. Wong recalls, “We took from this energy that came from the hippies, the Timothy Learys, rejecting everything that was post-Second World War ethics […] We were claiming space by taking up that space.”

For Wong, there was an immediate attraction to videography. “This new instant recording device was allowing people to make stuff outside of corporate media, outside of commercial feature media, out of broadcast, or formal film. Our work was low resolution and gritty. There was a lot of organized pushback to completely disrespect what we were trying to do with this technology,” he notes. Mentored by and working with Michael Goldberg at VIVO Media Arts, also known as the Satellite Video Exchange, Wong was at the forefront of paving a critical anti-commercial, anti-mainstream path for media art. “We were young people who were self-taught. There was no deep analysis on what was right or wrong — for us, it was all about doing. It was important for us to be able to share with each other. It was really the beginning of micromarketing and narrowcast,” he adds. In 1978, VIVO launched a magazine called Video Guide featuring international media work — something Wong describes as a representation of the greater “DIY culture” at the time. Within these networks, queer connections were being made: “People could list themselves as, you know, a lesbian feminist collective of colour [on the directory] and other people could see that. People would travel around and meet each other and eventually you had these connections being made [through media art],” Wong explains.

The Mainstreeter Era: Pioneering Media Arts

Born in Prince Rupert, British Columbia, in 1954, Wong first picked up a Portapak video camera when he was attending high school at Sir Charles Tupper Secondary. Wong’s experiences growing up with parents who work in separate cities reflect the stories of many children of first-generation immigrants. Wong remembers his family being labeled by people inside and outside of the Chinese community as not conforming to the “model minority myth.” He recalls a particular experience he had in high school that encapsulated this: “I remember getting called into the principal's office. The principal asked me, ‘what’s wrong with you and your siblings? Why don’t you act like the rest of your people?’”

With the onset of Canadian multiculturalism policy in the 1970s, stories like Wong’s, of racialized stereotypes and isolation, are often systematically erased. He had to negotiate and search for places to find belonging: “I did not fit into anyone’s prescribed expectations, from family to outside the family, but also the media.” He notes, “That was the catalyst to find other like-minded outsiders in the school system; in my case, it happened to be an attraction to the smokers, the drinkers, the artists. It was a natural place that allowed for creativity, queerness, and otherness. Here I could be [myself] and be okay.”

In the 1970s, Wong and his friends Kenneth Fletcher, Deborah Fong, Carol Hackett, Marlene MacGregor, Annastacia McDonald, Charles Rea, and Jeanette Reinhardt formed the Mainstreeters. They were a young art collective based around Vancouver’s Main Street, pushing back on the commodified and professionalized art world. Wong recalls, “We took from this energy that came from the hippies, the Timothy Learys, rejecting everything that was post-Second World War ethics […] We were claiming space by taking up that space.”

For Wong, there was an immediate attraction to videography. “This new instant recording device was allowing people to make stuff outside of corporate media, outside of commercial feature media, out of broadcast, or formal film. Our work was low resolution and gritty. There was a lot of organized pushback to completely disrespect what we were trying to do with this technology,” he notes. Mentored by and working with Michael Goldberg at VIVO Media Arts, also known as the Satellite Video Exchange, Wong was at the forefront of paving a critical anti-commercial, anti-mainstream path for media art. “We were young people who were self-taught. There was no deep analysis on what was right or wrong — for us, it was all about doing. It was important for us to be able to share with each other. It was really the beginning of micromarketing and narrowcast,” he adds. In 1978, VIVO launched a magazine called Video Guide featuring international media work — something Wong describes as a representation of the greater “DIY culture” at the time. Within these networks, queer connections were being made: “People could list themselves as, you know, a lesbian feminist collective of colour [on the directory] and other people could see that. People would travel around and meet each other and eventually you had these connections being made [through media art],” Wong explains.

“I didn’t see what I thought I was going to see, so I was quite incapable of seeing anything.”

(Re)turning to Southern China: Finding Self and Community

Wong went back to his family’s home in Southern China in 1982. It was Wong’s first visit to China and was only possible after his mother’s request was accepted by the Chinese government. For Wong, 1982 was a pivot point, “I was looking at where I come from, and what I am. It triggered a whole series of research, development, and projects […] These works are a gathering, and it’s very cathartic.” For both Wong and his mother, there was intense culture shock being back in Southern China. “I didn’t see what I thought I was going to see, so I was quite incapable of seeing anything. It was fragmented, there was no linear understanding,” Wong says. After his second trip to China in 1986, Wong created some of his first works addressing his new ways of understanding and seeing his identity, “I was working on Ordinary Shadows, Chinese Shade [1988], thinking what and who is this for?” These individual works led Wong to desire something more collaborative like Yellow Peril: Reconsidered, “I came back with questions and tried to find [Asian] artists with some of the same questions, or even answers. I was looking for work around that, and it was pretty slim.” Yellow Peril: Reconsidered (which was eventually printed as a book) was the first photo film and video collaboration between 25 Asian Canadian artists. “It was groundbreaking! People would ask, ‘Are you a producer, curator, or an artist?’ Thinking that you must be serving if you’re curating and creating. But it was about developing a network. Before that, there was really no community.” During this time, Wong described there being an excessive number of symposiums, publications in academia, and new policy papers regarding Asian-Canadian experiences. “I wanted to do work that wasn’t about talking. I wanted to create an exhibition where you would look at the work, not just reading about the possibility of what the work could be,” he adds.

“I wanted to do work that wasn’t about talking. I wanted to create an exhibition where you would look at the work, not just reading about the possibility of what the work could be.”

In 1992, during his residency at the Banff Centre in Alberta, Wong continued asking questions about his relation to Canada and its relation to China — creating work such as Chinaman’s Peak: Walking the Mountain. He recalls, “I was in Banff doing my residency, spending all my time mountain biking. And I started to wonder to myself, ‘Why the fuck is there a trail here called Chinaman’s peak in Canmore [Alberta]?’ Curiosity is what started it.”

Blending Milk and Water: Sex in the New World [1996] bridged Wong’s new perspectives to his older work Confused Sexual Views from 1984. Originally, Confused Sexual Views, a work addressing topics of bisexuality and AIDS, was banned from the Vancouver Art Gallery. The work was simply deemed “not art.” More than a decade later, conversations around sex and sexuality had changed in the public sphere. Blending Milk and Water: Sex in the New World was created after partners within the Chinese community in Vancouver had invited Wong to create an AIDS education tape. “It was made to succeed here, it was focused and had all that integrity with it. I wasn’t trying to make it for everyone,” he says. This work, intended to bring about educational awareness around AIDS to the city’s Mandarin and Cantonese-speaking communities, became popular on the international film festival circuit and was eventually shown at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

Blending Milk and Water: Sex in the New World [1996] bridged Wong’s new perspectives to his older work Confused Sexual Views from 1984. Originally, Confused Sexual Views, a work addressing topics of bisexuality and AIDS, was banned from the Vancouver Art Gallery. The work was simply deemed “not art.” More than a decade later, conversations around sex and sexuality had changed in the public sphere. Blending Milk and Water: Sex in the New World was created after partners within the Chinese community in Vancouver had invited Wong to create an AIDS education tape. “It was made to succeed here, it was focused and had all that integrity with it. I wasn’t trying to make it for everyone,” he says. This work, intended to bring about educational awareness around AIDS to the city’s Mandarin and Cantonese-speaking communities, became popular on the international film festival circuit and was eventually shown at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

Pictured is a still from Paul Wong’s Blending Milk and Water: Sex in the New World (1996), part of the Public Collections at the Vancouver Art Gallery.

Pictured is a still from Paul Wong’s Blending Milk and Water: Sex in the New World (1996), part of the Public Collections at the Vancouver Art Gallery.Pride in Chinatown: Queer Asian Art Today

Wong explains that visibly queer and Asian art was less frequent in the popular Vancouver art scenes in the late 90s. Since moving his studio to Chinatown in the last two and a half years, Wong has seen a powerful current of queer Asian creatives and activists within the neighbourhood and the city at large. In Chinatown, there has been a slow shift in alignment — with more radical queer movements, like media art collective Love Intersections and Asian drag house House of Rice. Curating the annual Pride in Chinatown event since 2018, bringing together queer Pan-Asian art and artists in the area, has been Wong’s most recent contribution to this movement. Wong recalls seeing a Pride flag in the neighbourhood for the first time as a part of the project, “I did Pride in Chinatown as part of my residency at [Dr.] Sun Yat Sun [Classical Chinese Garden]. It wasn’t an idea that was immediately welcomed. They didn’t know what it would look like, they didn’t know what it would mean, and now they are a committed partner to the project. I’m always trying to push for institutional change, change in forum, and change in audience.”

Wong has seen shifts in his personal relationship to Chinatown as a result of these currents and projects. “Chinatown, due to outside discrimination and politics, has created an unspoken expectation [of its community] to always be seen as a representation of the ‘model minority myth.’ This created a deadly silence when it came to progressive ideas. It was a fucked up patrichal space, with the clans and the associations, and it did not allow queer voices to speak… There was serious gatekeeping going on,” he articulated. With his history of doing work for the Chinese community in Vancouver and having a recognized name in the art world, Wong feels that it was right for him to be doing work related to Pride in Chinatown, “Nobody can ignore me when I ask for something [now]. I’m not just a youngster; I have a right to be here and to ask, and they don’t have a right to say no. I want to know what queer Asian art from Vancouver looks like, it’s a whole new terrain in some ways. That excites me.”

“It’s up to this new current [of Asian artists and activists] to contribute to Chinatown’s future. Pride in Chinatown is just one example of the possibilities.”

Gentrification in Vancouver’s Chinatown has seen various forms since the 1960s. In the past two decades, Asian-owned businesses in Chinatown have diminished at alarming rates. Wong notes, “You used to come to Chinatown to see your friends, see the doctor, play mahjong, go get your hair done, go to someone’s house and have tea. It’s so broken up [now], the 24-hour community here is gone. You used to come here and do it all.” With the COVID-19 pandemic and rising anti-Asian racism, even fewer Asian people are coming to Chinatown: “People are getting spit on and attacked. Why would you want any of your family coming down here?”

Wong sees the new current of Asian activists and artists as the movement that could keep what is left of Chinatown up, “It is up to those hanging on to rest power and get money from the shitheads (Vancouver City Planning and the Chinatown Business Association) that run this place into the ground. It’s up to this new current to contribute to Chinatown’s future. Pride in Chinatown is just one example of the possibilities.” He believes that there is a need for the continuation of Pride in Chinatown and projects like it, “I won’t be doing it next year, but I’ll be around as a consultant. I’ll look for people interested in organizing. I want to see [Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden] play a more active role and leadership role in shaping the future of Chinatown — it is a unique and important place.”

Wong sees the new current of Asian activists and artists as the movement that could keep what is left of Chinatown up, “It is up to those hanging on to rest power and get money from the shitheads (Vancouver City Planning and the Chinatown Business Association) that run this place into the ground. It’s up to this new current to contribute to Chinatown’s future. Pride in Chinatown is just one example of the possibilities.” He believes that there is a need for the continuation of Pride in Chinatown and projects like it, “I won’t be doing it next year, but I’ll be around as a consultant. I’ll look for people interested in organizing. I want to see [Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden] play a more active role and leadership role in shaping the future of Chinatown — it is a unique and important place.”

- Pride in Chinatown: http://www.prideinchinatown.com/

- Mainstreeters: Taking Advantage 1972-1982: https://takingadvantage.ca/

- Ordinary Shadows, Chinese Shade: https://paulwongprojects.com/portfolio/ordinary-shadows-chinese-shade/

- Yellow Peril: Reconsidered: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yellow_Peril:_Reconsidered

- Chinaman’s Peak: Walking the Mountain: http://paulwongprojects.com/portfolio/chinamans-peak-walking-the-mountain/

- Blending Milk and Water: Sex in the New World: https://paulwongprojects.com/portfolio/blending-milk-and-water-sex-in-the-new-world/

- Confused Seuxal Views: http://paulwongprojects.com/portfolio/confused-sexual-views/

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Serene Mitchell (米倚旋) is a Taiwanese-Canadian creative based in unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, and Sel̓íl̓witulh Nations (Vancouver), and Tiohtiá:ke (Montreal), currently completing her undergraduate degree in Asian North American history. On weekends you can find her skating with friends, at the local archives, or wandering around in Chinatown.

Serene Mitchell (米倚旋) is a Taiwanese-Canadian creative based in unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, and Sel̓íl̓witulh Nations (Vancouver), and Tiohtiá:ke (Montreal), currently completing her undergraduate degree in Asian North American history. On weekends you can find her skating with friends, at the local archives, or wandering around in Chinatown.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Paul Wong is a media-maestro making art for site-specific spaces and screens of all sizes. He is an award-winning artist and curator who is known for pioneering early visual and media art in Canada, founding several artist-run groups, leading public arts policy, and organizing events, festivals, conferences, and public interventions since the 1970s. Writing, publishing, and teaching have been an important part of his praxis. With a career spanning four decades, he has been an instrumental proponent to contemporary art.

Paul Wong is a media-maestro making art for site-specific spaces and screens of all sizes. He is an award-winning artist and curator who is known for pioneering early visual and media art in Canada, founding several artist-run groups, leading public arts policy, and organizing events, festivals, conferences, and public interventions since the 1970s. Writing, publishing, and teaching have been an important part of his praxis. With a career spanning four decades, he has been an instrumental proponent to contemporary art.