VOLUME 2 / ARTICLE 11 ︎

FINDING THE YIN TO HER YANG

A Trans Woman’s Emancipation From the Western Binary

An Interview with Bam Truong

Written by Viet Tran

Photography by Yang Shi

November 2020

Written by Viet Tran

Photography by Yang Shi

November 2020

Bam Truong with her father. Photos by Yang Shi, Make-Up by Brit Phatal.

Bam Truong with her father. Photos by Yang Shi, Make-Up by Brit Phatal. You may recognize Bam Truong from her time headlining Montreal’s Piknic Électronik or hosting the first-ever queer pan-Asian party as part of last year’s Fierté Montréal, but you won’t see her performing behind her mixing board any time soon. The recently retired DJ Bamboo Hermann is letting us know that she has left the nightlife behind to reconnect with her roots and commit to an alternative type of healing practice, having opened her acupuncture practice to clients this past July.

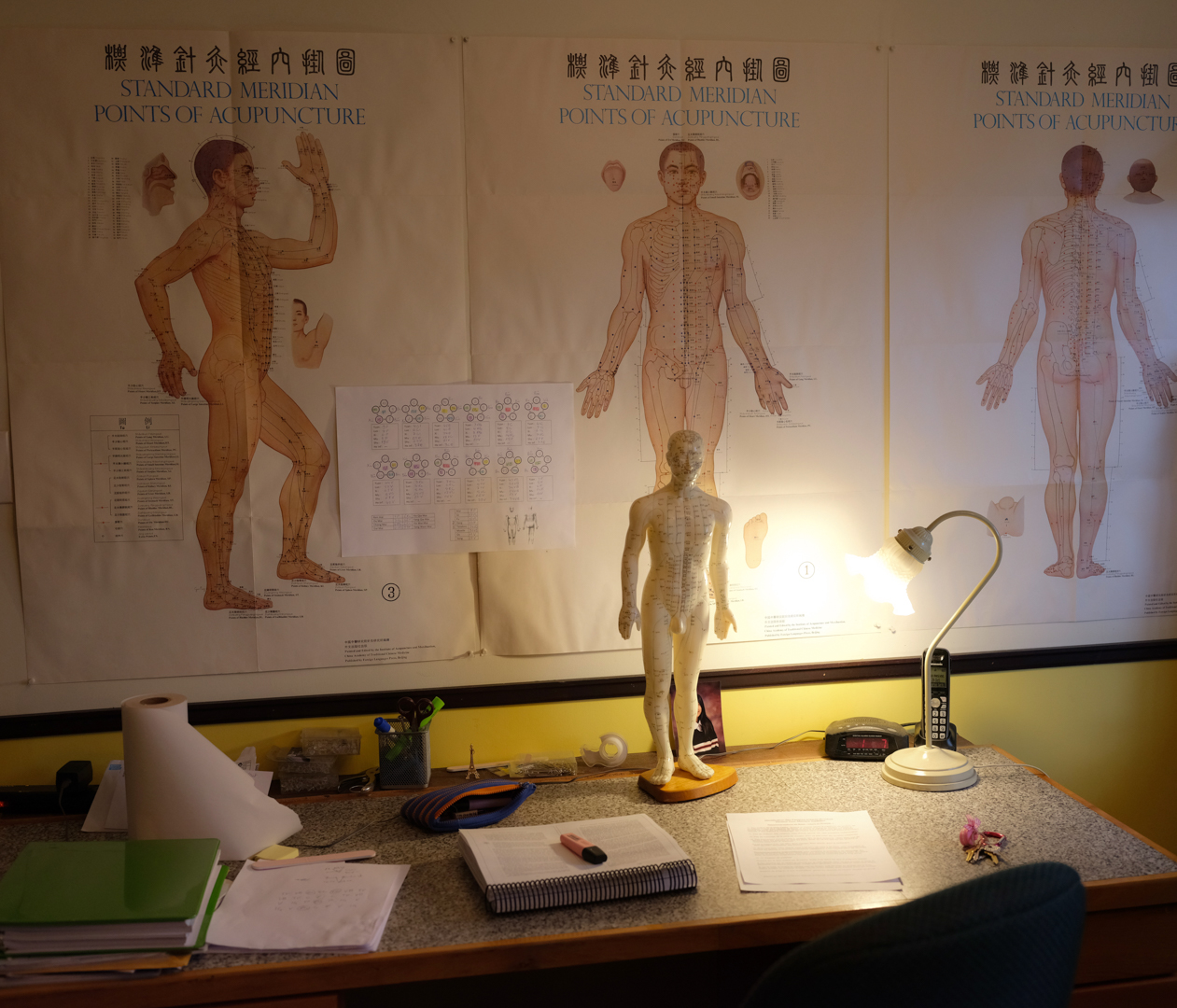

I caught up with Bam and her partner Yann in the sunlit treatment room of her acupuncture clinic, located just above her father’s duplex unit.

Through our conversation, I had the privilege of finding out more about the deeper meaning behind her work as an acupuncturist. She shared her wisdom on overcoming barriers to finding love in a world that is not always kind to those whose truth challenges the rigid-yet-fragile framework of heteropatriarchy, in a world that is too often violent and restrictive towards trans women of colour. Thankfully, we have stories like hers that spark hope.

“The Way” Of Self-Actualization

Viet: It’s easy to believe that one can live multiple lives within their lifetime after getting to know you. You’ve reinvented yourself while staying true to who you were along the way. Can you let us in on your journey of self-discovery?

Bam: Sure! To make things short, I’d say my journey has been a quest for self-actualization, an attempt at realizing the implicit promise of happiness that came with the migration of my parents from Vietnam to the West. It’s been a relentless existential journey to reach my full potential as an individual, beyond the social constructs of race, gender and sexuality.

I first studied architecture at McGill University. Having studied science in high school with the plan of getting into med school (like many second-generation Asians I'm sure!) and being artistically inclined, architecture seemed like the perfect “compromise” between science and art. After my degree, I was still dissatisfied in my artistic needs. I went on to study Fine Arts at Concordia for two years, where I eventually dropped out to travel and live abroad in Thailand for a year —a life-changing year that allowed me to reconnect with my Southeast Asian heritage. I then Paris where I worked for two years as an interior designer.

I went back to school in 2008 to get my Masters of Architecture in Lausanne, Switzerland. My real plan was actually to move to London for its thriving nightlife and club culture; I had always been a clubhead with a passion for electronic music. Getting my degree was a way to make sure I’d be able to sustain myself in London while exploring its nightlife. At the time, London looked like a culturally diverse city where individuals could become true to themselves and connect beyond usual social conventions — the ideal place for a second-generation immigrant kid like me who was eager to bypass the model minority integration path. UK electronic music embodied that ideal in how it succesfully mixed influences from its different cultures, transcending them into something new, uniting, and exciting.

I caught up with Bam and her partner Yann in the sunlit treatment room of her acupuncture clinic, located just above her father’s duplex unit.

Through our conversation, I had the privilege of finding out more about the deeper meaning behind her work as an acupuncturist. She shared her wisdom on overcoming barriers to finding love in a world that is not always kind to those whose truth challenges the rigid-yet-fragile framework of heteropatriarchy, in a world that is too often violent and restrictive towards trans women of colour. Thankfully, we have stories like hers that spark hope.

“The Way” Of Self-Actualization

Viet: It’s easy to believe that one can live multiple lives within their lifetime after getting to know you. You’ve reinvented yourself while staying true to who you were along the way. Can you let us in on your journey of self-discovery?

Bam: Sure! To make things short, I’d say my journey has been a quest for self-actualization, an attempt at realizing the implicit promise of happiness that came with the migration of my parents from Vietnam to the West. It’s been a relentless existential journey to reach my full potential as an individual, beyond the social constructs of race, gender and sexuality.

I first studied architecture at McGill University. Having studied science in high school with the plan of getting into med school (like many second-generation Asians I'm sure!) and being artistically inclined, architecture seemed like the perfect “compromise” between science and art. After my degree, I was still dissatisfied in my artistic needs. I went on to study Fine Arts at Concordia for two years, where I eventually dropped out to travel and live abroad in Thailand for a year —a life-changing year that allowed me to reconnect with my Southeast Asian heritage. I then Paris where I worked for two years as an interior designer.

I went back to school in 2008 to get my Masters of Architecture in Lausanne, Switzerland. My real plan was actually to move to London for its thriving nightlife and club culture; I had always been a clubhead with a passion for electronic music. Getting my degree was a way to make sure I’d be able to sustain myself in London while exploring its nightlife. At the time, London looked like a culturally diverse city where individuals could become true to themselves and connect beyond usual social conventions — the ideal place for a second-generation immigrant kid like me who was eager to bypass the model minority integration path. UK electronic music embodied that ideal in how it succesfully mixed influences from its different cultures, transcending them into something new, uniting, and exciting.

“At first glance, Traditional Chinese Medicine might seem at first disconnected from DJing, but I see them both as means to promoting well-being and relief by working through the body and the senses.”

Once in London, I soon integrated into the East London queer scene that had a bit of a cultural boom from 2005 to 2015. I gradually went from the dancefloor to the DJ booth as Bamboo Hermann, which was when I started my transition. Becoming a DJ and finding myself as a trans woman was in a sense the culmination of the self-actualization process I started a few years before, proving to myself that my voice mattered. Within the context of the quasi-absence of Asian role models within contemporary Western culture, that meant a lot to me.

Eventually London got gentrified to a point where the queer cultural nightlife had started to decline. I then decided to quit architecture to focus on music for a while until I came back to Montreal in 2016 for family reasons. I decided to retrain in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), wanting to settle down and find a more balanced lifestyle.

At first glance, Traditional Chinese Medicine might seem at first disconnected from DJing, but I see them both as means to promoting well-being and relief by working through the body and the senses. I finally graduated this year and started my acupuncture practice in June, while definitely turning the page on DJing. The COVID-19 crisis also convinced me that it was the right moment to do so.

V: I enjoy looking at your candid family photos on Instagram. How has your relationship with your family evolved over time?

B: My coming out as a gay guy at 18 years old went pretty well with my family. Having grown up in downtown Montreal, I was exposed early on to the LGBTQ+ scene. My father, who worked with the public with a majority of Quebecer clients, was familiar with urban Quebec reality, which includes a certain openness towards LGBTQ+ people. For those reasons, my coming out as a gay person wasn’t a problem for him. However, it took a bit more time for my mother to come to terms with who I was — I think that i was mainly because we were living in different countries for a few years. Because our long-distance relationships did not allow for her to see me coming into adulthood, it took her more time to understand me. After a year or two, she accepted this part of who I was.

Coming out as a trans woman at 35 has been trickier. Because I myself was unsure of where I stood within the gender spectrum, my transition has been a very slow and gradual process, unlike my sexual orientation — that was pretty clear to me very early in my life. My strategy for coming out was to reveal myself as much as I could on my social media platforms, using pictures of me in cross-dress in order for my family to see me for who I was. But that strategy didn’t quite work out the way I planned. At first, my parents thought that it was mainly a drag act, and my mother was amused by my new “artistic” endeavours.

Now, however, even after having legally changed my gender marker to female, I am still struggling to make them understand that I am a trans woman. The mainstream essentializing binary discourse on trans people being “born in the wrong body” is the main argument my parents use today to question my transness: “You are not really trans since you didn’t want to be a girl as a child!” I think it’s a matter of time, as with most things, before they finally understand who I am on a purely conceptual level. I am very lucky and grateful however that their love for me was never a question.

Transforming Body/ies

V: Many people are unaware of the particularities and differences of dating as a queer Asian person. I appreciate you making yourself available to share the insights of your personal experiences.

B: My dating experiences as a cis gay guy and as a transgender woman have both been tainted by the pervasive orientalist prejudice against Asians. Orientalism, which I interpret as a form of gendered racism (i.e. the essentializing of Asians as being inherently feminine) has affected the way people perceive me as a sexual being both as a man and a woman, and has ultimately shaped my own sexuality and desires.

When I was dating as an Asian man, I was outraged by the internalized femphobia and racism projected onto Asian men. Back in the 2000s when I came out, there wasn’t much awareness of racism within the gay community. The Gay Village was very much White and masc4masc in its aesthetics and values, with very little to no room for gender and racial diversity. It was shocking to see the amount of Grindr profiles that blatantly stated “No Asians, no fems” in their profile bios, and I would get into so many pointless arguments to try to make people aware of how racist that was. On the other end of the Orientalist bias, I was also wary of guys with a fetish for Asians —“rice queens” and such— who saw me as one of many in their harem of Asian delicacies. I felt that no matter how hard I tried, the orientalist lens would always distort to some degree or another my intimate relationships.

Eventually London got gentrified to a point where the queer cultural nightlife had started to decline. I then decided to quit architecture to focus on music for a while until I came back to Montreal in 2016 for family reasons. I decided to retrain in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), wanting to settle down and find a more balanced lifestyle.

At first glance, Traditional Chinese Medicine might seem at first disconnected from DJing, but I see them both as means to promoting well-being and relief by working through the body and the senses. I finally graduated this year and started my acupuncture practice in June, while definitely turning the page on DJing. The COVID-19 crisis also convinced me that it was the right moment to do so.

V: I enjoy looking at your candid family photos on Instagram. How has your relationship with your family evolved over time?

B: My coming out as a gay guy at 18 years old went pretty well with my family. Having grown up in downtown Montreal, I was exposed early on to the LGBTQ+ scene. My father, who worked with the public with a majority of Quebecer clients, was familiar with urban Quebec reality, which includes a certain openness towards LGBTQ+ people. For those reasons, my coming out as a gay person wasn’t a problem for him. However, it took a bit more time for my mother to come to terms with who I was — I think that i was mainly because we were living in different countries for a few years. Because our long-distance relationships did not allow for her to see me coming into adulthood, it took her more time to understand me. After a year or two, she accepted this part of who I was.

Coming out as a trans woman at 35 has been trickier. Because I myself was unsure of where I stood within the gender spectrum, my transition has been a very slow and gradual process, unlike my sexual orientation — that was pretty clear to me very early in my life. My strategy for coming out was to reveal myself as much as I could on my social media platforms, using pictures of me in cross-dress in order for my family to see me for who I was. But that strategy didn’t quite work out the way I planned. At first, my parents thought that it was mainly a drag act, and my mother was amused by my new “artistic” endeavours.

Now, however, even after having legally changed my gender marker to female, I am still struggling to make them understand that I am a trans woman. The mainstream essentializing binary discourse on trans people being “born in the wrong body” is the main argument my parents use today to question my transness: “You are not really trans since you didn’t want to be a girl as a child!” I think it’s a matter of time, as with most things, before they finally understand who I am on a purely conceptual level. I am very lucky and grateful however that their love for me was never a question.

Transforming Body/ies

V: Many people are unaware of the particularities and differences of dating as a queer Asian person. I appreciate you making yourself available to share the insights of your personal experiences.

B: My dating experiences as a cis gay guy and as a transgender woman have both been tainted by the pervasive orientalist prejudice against Asians. Orientalism, which I interpret as a form of gendered racism (i.e. the essentializing of Asians as being inherently feminine) has affected the way people perceive me as a sexual being both as a man and a woman, and has ultimately shaped my own sexuality and desires.

When I was dating as an Asian man, I was outraged by the internalized femphobia and racism projected onto Asian men. Back in the 2000s when I came out, there wasn’t much awareness of racism within the gay community. The Gay Village was very much White and masc4masc in its aesthetics and values, with very little to no room for gender and racial diversity. It was shocking to see the amount of Grindr profiles that blatantly stated “No Asians, no fems” in their profile bios, and I would get into so many pointless arguments to try to make people aware of how racist that was. On the other end of the Orientalist bias, I was also wary of guys with a fetish for Asians —“rice queens” and such— who saw me as one of many in their harem of Asian delicacies. I felt that no matter how hard I tried, the orientalist lens would always distort to some degree or another my intimate relationships.

“ How much of the empowerment I thought I had found as an Asian trans woman was in fact due to the reinforcement of the “China doll” trope?”

After making our way around winding corridors surrounded by crimson red doors, we meet Bam and her partner Yann, who is not a stranger to needles.

When I started exploring my gender identity, cross-dressing felt empowering. I felt that rather than being ashamed of being Asian and feminine, I would own it by being the most fabulous Asian feminine creature I could be! However, the further I went into my transition, I soon found myself caught again inside the orientalist fetishist trap; how much of the seduction power I had gained was in fact only the shine of the other side of the female orientalist coin? How much of the empowerment I thought I had found as an Asian trans woman was in fact due to the reinforcement of the “China doll” trope? And with that trope, how much respect and consideration as a human being did I really gain?

Orientalism is a powerful, double-edged white supremacist mechanism: on one end it emasculates Asian men, while on the other, it turns Asian women into passive exotic sexual objects. Through the gendering of race it surrenders Asians to the male gaze of white patriarchy by taking away agency over our racialised bodies and sexualities. It is still an on-going process of untangling myself from the white gaze and reclaim my own sexuality and desires, which isn't always easy to do!

How did I find love? Three years ago, I met the most loving, caring and self-accepting “rice queen trans lover” I could find! I had been struggling for the longest time to meet a cis man that could come to terms with his attraction for trans women. My boyfriend is one of the few I’ve met who are out and proud of loving trans women, and hopefully more of the younger generation of cis men will step up and step forward alongside trans women. My boyfriend is mixed-race of Haitian and Quebecois descent, having had experienced his own share of black fetishization. Luckily, as a POC couple, we are able to exist and love each other away from the toxic fetishist white gaze — other than the one we’ve internalized, but that’s another story.

V: You’ve come to understand and embrace your true self in its wholeness in a world in which it is often easier to divide things in binary systems, to think in polarized ways.

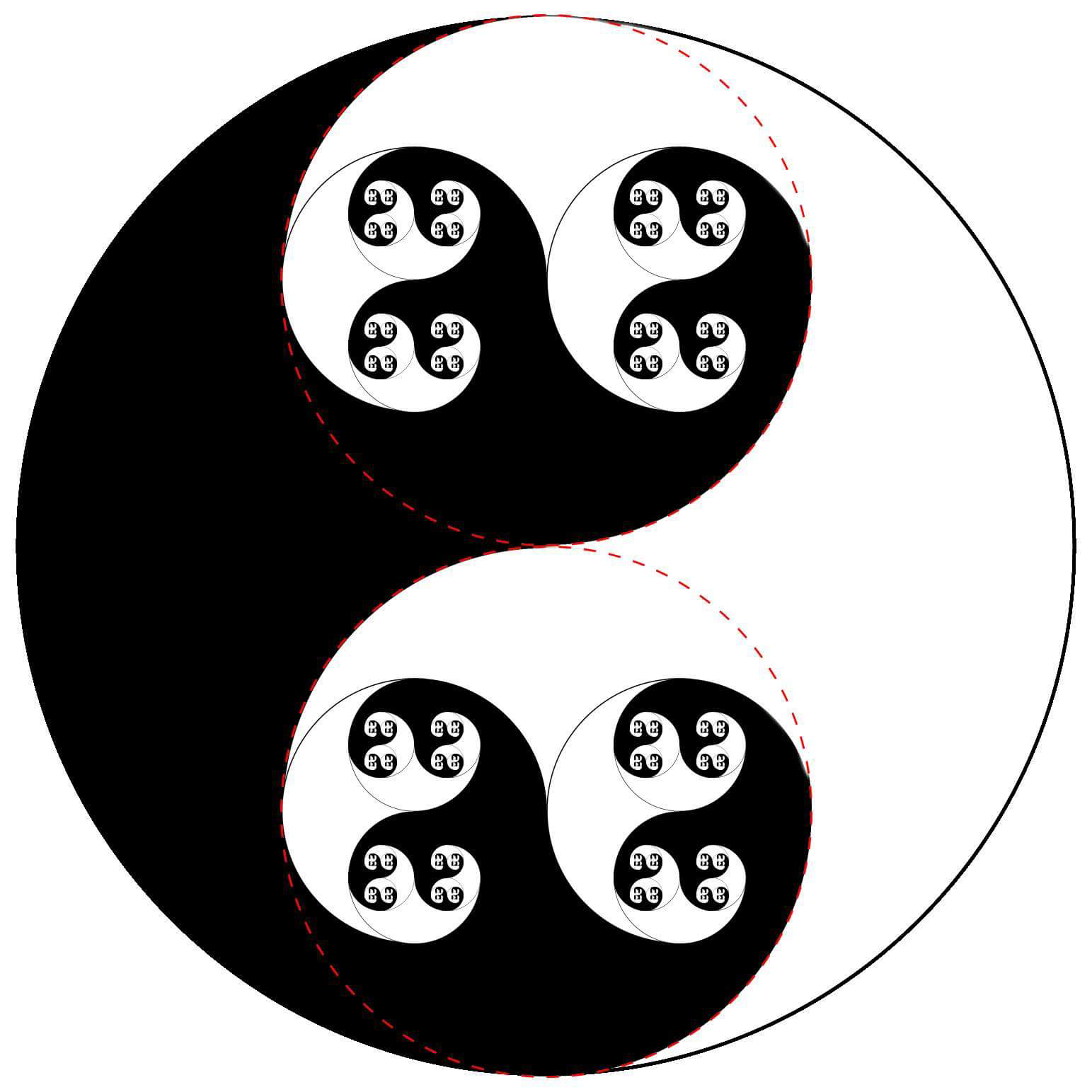

B: My identity as a whole is a combination of a multitude of cultural experiences: raised in Switzerland and Quebec, of Vietnamese-Chinese descent, non-binary trans-feminine and queer. I had to make sense of who I am outside of any binary notion of identity. In a society that has a hard time making space for in-betweens, I had to draw from my Chinese heritage in order to find a conceptualization of the world in which I made sense. Daoism and the founding principle of the Yin Yang were instrumental in that process: Daoist philosophy sees the Universe as a constant and dynamic interplay between two poles which creates infinite possible realities that are never absolute nor fixed in time. The notion of life being in constant flux is central to how I see myself: my gender identity is not an absolute given, but rather an evolving concept through time, places, experiences, and relationships.

Orientalism is a powerful, double-edged white supremacist mechanism: on one end it emasculates Asian men, while on the other, it turns Asian women into passive exotic sexual objects. Through the gendering of race it surrenders Asians to the male gaze of white patriarchy by taking away agency over our racialised bodies and sexualities. It is still an on-going process of untangling myself from the white gaze and reclaim my own sexuality and desires, which isn't always easy to do!

How did I find love? Three years ago, I met the most loving, caring and self-accepting “rice queen trans lover” I could find! I had been struggling for the longest time to meet a cis man that could come to terms with his attraction for trans women. My boyfriend is one of the few I’ve met who are out and proud of loving trans women, and hopefully more of the younger generation of cis men will step up and step forward alongside trans women. My boyfriend is mixed-race of Haitian and Quebecois descent, having had experienced his own share of black fetishization. Luckily, as a POC couple, we are able to exist and love each other away from the toxic fetishist white gaze — other than the one we’ve internalized, but that’s another story.

V: You’ve come to understand and embrace your true self in its wholeness in a world in which it is often easier to divide things in binary systems, to think in polarized ways.

B: My identity as a whole is a combination of a multitude of cultural experiences: raised in Switzerland and Quebec, of Vietnamese-Chinese descent, non-binary trans-feminine and queer. I had to make sense of who I am outside of any binary notion of identity. In a society that has a hard time making space for in-betweens, I had to draw from my Chinese heritage in order to find a conceptualization of the world in which I made sense. Daoism and the founding principle of the Yin Yang were instrumental in that process: Daoist philosophy sees the Universe as a constant and dynamic interplay between two poles which creates infinite possible realities that are never absolute nor fixed in time. The notion of life being in constant flux is central to how I see myself: my gender identity is not an absolute given, but rather an evolving concept through time, places, experiences, and relationships.

“ My gender identity is not an absolute given, but rather an evolving concept through time, places, experiences, and relationships.”

In the same way, my sense of ethnic-national identity has been shaped in relation to the places where I lived—Europe, North-America, Asia. Traveling was a way for me to experiment with my sense of self, gauging how I was perceived in different cultural contexts, and drawing from those experiences in order to build my own identity. Not unlike a scientific experiment, variables of context and culture are changed in order to determine the constant throughout.

For instance, I understood very early on that my gender identity as an Asian man was a social construct that would vary hugely from one place to another. In the West, orientalist prejudice against Asian masculinity made me feel undervalued as a man and therefore invisible. Living in Thailand however, away from Western racism, I was perceived in a completely different way; being light-skinned and having looks that fitted Asian pop culture standards of male beauty, I noticed how much Thai society would make space for me as a young good-looking Asian man. All of a sudden, I wasn’t the emasculated invisible Asian “boy” I was in Canada anymore, but had become an attractive “man” fitting ideals of Asian male beauty — with new-found privileges and even admiration from society.

In London, the reverse experience happened. This time, the variable wasn’t culture, but gender itself. As I started transitioning within the context of a Western culture with orientalist biases, I noticed the change in desirability and attention I would get from transitioning from an emasculated Asian boy to a desirable Asian trans woman; I suddenly felt that I was “noticeable”, that people would pay attention to me, even if only superficially. As discussed earlier, desirability sadly does not equal respectabilitysomething all women realize at some point in their life, a realization of woman objectification exacerbated by the addition of orientalist and trans fetishizations.

Moxibustion is a Chinese medicine technique used to heat the body by burning mugwort.

Needles are used in acupuncture to stimulate specific points along energetic paths called meridians.

Healing and Wholeness

V: The work of an acupuncturist remains mysterious for a lot of people, myself included. What should one know about this traditional Chinese practice if one is interested in engaging with this form or healing?

B: Acupuncture can help alleviate symptoms of various conditions, whether it be musculo-skeletal issues and pain or internal conditions such as digestive, fertility, uro-genital issues or those related to emotions such as migraine, insomnia, anxiety, depression, stress etc. Some people come with some apprehension of the needles. The needles are actually really thin (about a quarter of a mm-thick) and there is usually no pain apart from a brief small pinching sensation as the needle goes through the skin. The sensation once the needle is in can be quite varied — from a small tingling sensation to a feeling of warmth, or the sensation of some energy flowing between acupuncture points and to other parts of the body. Most people come out of an acupuncture session feeling relaxed, centred, and more in tune with their bodies.

In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), physical, emotional, and spiritual health are one interdependent whole. If one aspect is affected or unbalanced, the others will suffer inevitably. Therefore, from such a perspective, when we work on the body, we simultaneously work on our emotional and spiritual wellbeing. There is the Daoist notion of “Ming” in TCM, that can be translated as “destiny” or “heavenly mandate”. It’s the notion that every being has a heavenly purpose to achieve on Earth during their lifetime. Chinese medicine’s ultimate goal is to help people align themselves with their “Ming” by removing physical, emotional, and spiritual disorders that might hinder the achievement of one’s “destiny”.

“Yin and Yang is a Daoist conceptual framework composed of two opposites, but mutually interconnected forces that give life to all things.”

V: I love the Yin Yang symbol used in your brand. Can you explain to me what it means to you?

B: The Yin Yang symbol I used, also known as “Taiji Tu” or the “supreme ultimate”, is an older version from the 16th Century drawn by Daoist philosopher Lai Zi De. It is composed of the Yin and Yang swirling between two circles. The central circle represents “Wuji” or the infinite state of “non-being” that precedes and from which stem the Yin and the Yang. The outer circle represents the unity encompassing all phenomena of the universe. Yin and Yang is a Daoist conceptual framework composed of two opposite, but mutually interconnected forces that give life to all things. The notion of constant change and dynamic interdependence between these forces has allowed me to better understand myself outside of the Western binary that sees the world in mutually exclusive opposites fixed in time. It’s been a liberating change of paradigm, or rather a return to a philosophical heritage, within which I felt immediately home.

B: The Yin Yang symbol I used, also known as “Taiji Tu” or the “supreme ultimate”, is an older version from the 16th Century drawn by Daoist philosopher Lai Zi De. It is composed of the Yin and Yang swirling between two circles. The central circle represents “Wuji” or the infinite state of “non-being” that precedes and from which stem the Yin and the Yang. The outer circle represents the unity encompassing all phenomena of the universe. Yin and Yang is a Daoist conceptual framework composed of two opposite, but mutually interconnected forces that give life to all things. The notion of constant change and dynamic interdependence between these forces has allowed me to better understand myself outside of the Western binary that sees the world in mutually exclusive opposites fixed in time. It’s been a liberating change of paradigm, or rather a return to a philosophical heritage, within which I felt immediately home.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Viet Tran is the Editor-in-chief of Sticky Rice Magazine and a resident psychiatrist at McGill University who is always looking to better understand human suffering and the power of (re)connecting.

ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHER

Yang Shi is a multidisciplinary creative and a lifestyle editor for Sticky Rice Magazine. Born in China and raised in Montreal, she loves food, rock ’n roll, and a good meme.