VOLUME 3 / ARTICLE 05 ︎

By Nikki Celis

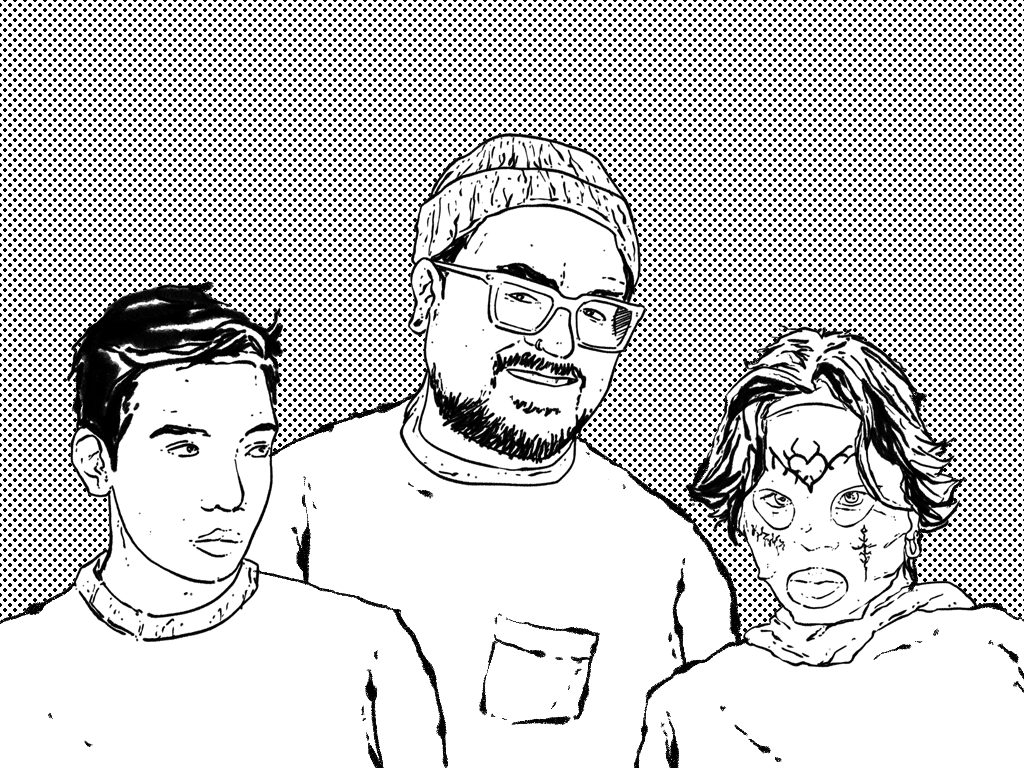

Illustration Portraits by Elie Chap

October 30th 2023

![]()

In Conversation: Filipinos on the Search for Stability

Uncovering the past to tell stories for aspiring futures.

By Nikki Celis

Illustration Portraits by Elie Chap

October 30th 2023

What does the future look like for a community that feels like they’re never good enough? It’s about uncovering the past and telling our stories.

Thinking about the future is such an interesting—and highly personal—prospect. For some, it’s a future built on admittedly orientalized mythologies. And in a way, you can see the concept and its often hedonistic and superficial affects at play.

In fashion, you’ll see it in the use of tech wear. Step into a club and you’ll see futurism, cyberpunk, and whatever other umbrella that exists is front and center in the music scene. Food? You’ll see it in highly pretentious (in my subjective opinion) displays of food deconstruction in high-end establishments.

None of this is a bad thing, mind you. But as a Filipino born under working-class circumstances, I envision something else entirely.

As a kid, I thought the epitome of fine dining was eating at Swiss Chalet or Olive Garden (because who doesn’t love bottomless salads). Sbarro? That’s some fine Italian food right there. My family was a fractured one, and the only semblance of a future I could see was one where we could live with a minutia of normalcy.

In the Philippines, roughly 18.1% of Filipinos live under the poverty line (2021). My mother was one of those people. 18.1% isn’t something to be glossed over either, considering that there are at least 117 million Filipinos living in the motherland. Some live in dumps, eating scraps from garbage bins. Others live in makeshift barangays and graveyards.

What kind of future do you think they see when they struggle to survive on the daily? When put into this context, the prospect is rooted in one’s level of privilege.

In my interviews with Khrysta Lloren—an old friend of mine from Cebu who now lives in Vancouver as an animator under the alias NOFAC3—art activist Allan Matudio, and chef Dre Mejia, when approached with the idea of what the future might be, it all circled back to achieving a sense of stability. It’s a form of stability based on a collective desire to look into the past to deliver new and often radical expressions.

But to do so, “we need storytellers to tell our stories,” says Dre.

![]() Khrysta Lloren, NOFAC3, by Elie Chap

Khrysta Lloren, NOFAC3, by Elie Chap

The following interview is a curated series of individual conversations that have been edited, compiled, and condensed. The core messages and ideas remain intact while shortened for brevity.

NIKKI: When it comes to our future, what does the future Filipino look like?

KHRYSTA: That’s such a profound thing to think about.

DRE: I think we’re all at a similar place in discovering our identities, especially with food [and art]. We’re trying to promote what we’ve learned to the younger generations and to get them to realize their sense of belonging. I want them to see that Filipino food is amazing—that it’s nourishing—that it’s cool. There’s no shame or guilt about it.

KHRYSTA: [Conceptually], if you think about the modern day and how we perceive “futurism” or “cyberpunk,” that’s not [our trajectory] even if it’s happening in other places.

NIKKI: I guess to Dre’s point, it’s about being comfortable in your skin. It’s interesting because I think many Asian communities in the diaspora area are already at—or even past—that stage. We’re still trying to get to that point.

DRE: Exactly.

ALLAN: My immediate network is involved in building platforms and advocating for change but the reality is, that new Filipinos arrive every day and they often start from scratch. We’re building so much, but the truth is—even though we are taking space, participating in important conversations, offering services, and creating art, most are unaware or don't have access to this.

NIKKI: Allan makes a great point about stability because, within art, we need to obtain the privilege to do artistic works and to have the freedom to break out of that mentality of just trying to survive.

DRE: I feel that there are not enough leaders out there. We need role models that push that ideology.

NIKKI: What’s holding us back?

DRE: The way we’re exposed to that Filipino crab mentality. I think with the current generation, they’re more open to deleting it.

ALLAN: The thing is—and this relates to our community work—work like this never ends. Because of how our migration channels work, we’re always going to need to help new families. So, [there are a lot of different] motivations and obligations. People come here for a better life, but that doesn’t necessarily relate to art. Art is a tertiary thought.

KHRYSTA: When you’re busy surviving, do you really have time to [pause and] reflect? Time is precious. And with capitalism, time is money. And the less money you have, the less time you have to think.

ALLAN: It takes maybe a generation or two to be able to have the curiosity to at least consume art or be exposed to it. So when it comes to the future of the Filipino, I’d love to imagine someone who is radical and influenced by many past artists. But the truth is, how possible is that?

You need to have a sort of entitlement to access that mindset.

NIKKI: A lot of migrants have working or below-working-class backgrounds. For example, when my mom came here, she was at the bottom of the food chain in the Philippines. There’s this sort of dynamic at play in terms of poverty, where there will always be someone poorer than you. When did she ever have the opportunity to think about art—when she was trying to live and simultaneously send that money to the Philippines?

ALLAN: But even then, even if you could live comfortably, who says that you’re going to jump into art, right?

NIKKI: Exactly. Dre, for non-Filipino readers, what’s the crab mentality?

DRE: It’s when one Filipino thinks they’re better than other Filipinos. It’s a competitive cycle where we can get the approval of [other people in the community]. It comes from how older generations grew up, where everyone was on their own. They could only support their immediate family.

NIKKI: When you look at other communities, they don’t really have that.

DRE: Yeah, they take pride in supporting their community members—promoting their businesses and each other.

![]() Dre Mejia

by Elie Chap

Dre Mejia

by Elie Chap

NIKKI: So what does stability mean for you?

DRE: It’s to have our presence more known. Recently, people are starting to understand that we’re not just a generalization but a specific Asian [with our unique history].

KHRYSTA: This question has so many layers. That's why it's so hard to crack and that's why it's so difficult as well to solve.

NIKKI: When it comes to looking at the future, it’s about embracing your past. What comes to mind?

DRE: It’s about being older and wiser. Now I can look back on my experiences and that if I knew the stuff I do now, things could have been better or progressed faster. You see that now with how we’re teaching the youth by sharing what we’ve learned.

NIKKI: It’s interesting because not many of us know that we’ve been in North America for centuries, going way back to the 1600s! And it’s a shame that we’ve been here so long, but we don’t have the same cultural foundation as the Chinese communities. Maybe that comes down to the crab mentality. Maybe that comes down to other things.

KHRYSTA: You know what we have? Survival skills. In Physical 100, there’s a rock climber that’s really skilled because he saves lives. He’s got real muscles from saving people and surviving. With Filipinos, we’re the same. We’ve got thick skin [from having to survive], from having to learn the language to understand how to live. And it’s such a common story that we have films and TV shows about our migration patterns.

I feel like the future of the Philippines is very similar to how we live right now. Even just ten years ago with how we’ve adapted to different presidents with different intentions. Adaptability—how we can immediately react to situations—is our strongest asset, where we can build things out of nothing.

NIKKI: We’re scrappers. But how do we go beyond just trying to survive?

KHRYSTA: I feel like we shouldn’t solely give in to the [stereotype] that Filipinos are hard workers. We think that by working more, we’ll get a bigger reward from working that much harder. Different colonizers sold us their dreams, and today Filipinos go abroad to chase the American dream—but once you get there, it’s an unforgiving place. There’s a movie about that called Perfumed Nightmare (1977).

NIKKI: We give our bodies away.

KHRYSTA: That’s the thing I can’t stop thinking about. The only way [to have a future] is to look back at where we came from and analyze what the fuck went wrong. Now, people are learning how that’s influenced by all the people who’ve invaded and colonized us. With stability, I’m [thinking] about it in a way that’s more than [just practicality or financial stability]. It’s the attitude.

NIKKI: So how do we communicate that?

KHRYSTA: I’m trying to incorporate [these ideas] with my art. When I used to paint, I was painting about [my experience living in] the Philippines. I’d talk to other Filipinos in art school, and they’d [say the same thing]. Like, what does that mean?

ALLAN: A lot of what I do is related to my identity. Specifically, that means reconnecting to our traditions and mythologies because they influence our mannerisms and culture. But it’s also important to look at what more modern artists have been doing and see what messages they shared 10 or 20 years ago. But you need to have the skills to do research. Early in my practice, I was trying to learn about Filipinos in Montreal. Obviously, I Googled it. [At that time], the results weren’t great. But, what surprised me was going into university libraries and reading academic papers from Filipino graduates that focused on the community. I mean, that, too, comes with having the privilege of getting into higher education.

KHRYSTA: You know, it’s like the idea of being Filipino and making art about our country versus being Filipino and making art in general. It’s something so deeply ingrained in us. For me, I’ve got to pour my heart and soul into a claymation short film to tell people about our realities.

NIKKI: Dre, in terms of food, how does that look?

DRE: I’ve always wanted to introduce Filipino food to the masses. Before, I thought the way to do it was through fusion cuisine and turning Filipino food into more Westernized dishes. But, as I got older, especially with today’s palates and food diversity, there’s more [room for authenticity].

Now, I’ve learned more to appreciate the cooking of my past. The food from my mother and my grandmothers. From my dad’s cooking, too. Now, my food is more “nostalgic cooking,” more true-to-heart—making you reminisce about the past.

![]() Allan Matudio

by Elie Chap

Allan Matudio

by Elie Chap

NIKKI: It all starts with intention. We need to be stable enough to find the kind of initiative—the courage—to get past that and create these role models that will inspire these new expressions.

KHRYSTA: Newer generations have a better possibility of making change.

DRE: Definitely. Our food has a story to tell. And we need those storytellers to tell our stories.

KHRYSTA: Whether it's from your dream, or nightmare, or reality, if you want it, you can just tell a story. The hardest part of storytelling is uncovering our roots and finding something that inspires you.

ALLAN: [It comes down to us, too]. At a young age, we’ve been taught generations ago that we’re not good enough the way we are. We need to work on addressing and healing intergenerational trauma so that the youth can dream of whatever future they want.

Thinking about the future is such an interesting—and highly personal—prospect. For some, it’s a future built on admittedly orientalized mythologies. And in a way, you can see the concept and its often hedonistic and superficial affects at play.

In fashion, you’ll see it in the use of tech wear. Step into a club and you’ll see futurism, cyberpunk, and whatever other umbrella that exists is front and center in the music scene. Food? You’ll see it in highly pretentious (in my subjective opinion) displays of food deconstruction in high-end establishments.

None of this is a bad thing, mind you. But as a Filipino born under working-class circumstances, I envision something else entirely.

As a kid, I thought the epitome of fine dining was eating at Swiss Chalet or Olive Garden (because who doesn’t love bottomless salads). Sbarro? That’s some fine Italian food right there. My family was a fractured one, and the only semblance of a future I could see was one where we could live with a minutia of normalcy.

In the Philippines, roughly 18.1% of Filipinos live under the poverty line (2021). My mother was one of those people. 18.1% isn’t something to be glossed over either, considering that there are at least 117 million Filipinos living in the motherland. Some live in dumps, eating scraps from garbage bins. Others live in makeshift barangays and graveyards.

What kind of future do you think they see when they struggle to survive on the daily? When put into this context, the prospect is rooted in one’s level of privilege.

In my interviews with Khrysta Lloren—an old friend of mine from Cebu who now lives in Vancouver as an animator under the alias NOFAC3—art activist Allan Matudio, and chef Dre Mejia, when approached with the idea of what the future might be, it all circled back to achieving a sense of stability. It’s a form of stability based on a collective desire to look into the past to deliver new and often radical expressions.

But to do so, “we need storytellers to tell our stories,” says Dre.

The following interview is a curated series of individual conversations that have been edited, compiled, and condensed. The core messages and ideas remain intact while shortened for brevity.

NIKKI: When it comes to our future, what does the future Filipino look like?

KHRYSTA: That’s such a profound thing to think about.

DRE: I think we’re all at a similar place in discovering our identities, especially with food [and art]. We’re trying to promote what we’ve learned to the younger generations and to get them to realize their sense of belonging. I want them to see that Filipino food is amazing—that it’s nourishing—that it’s cool. There’s no shame or guilt about it.

KHRYSTA: [Conceptually], if you think about the modern day and how we perceive “futurism” or “cyberpunk,” that’s not [our trajectory] even if it’s happening in other places.

NIKKI: I guess to Dre’s point, it’s about being comfortable in your skin. It’s interesting because I think many Asian communities in the diaspora area are already at—or even past—that stage. We’re still trying to get to that point.

DRE: Exactly.

ALLAN: My immediate network is involved in building platforms and advocating for change but the reality is, that new Filipinos arrive every day and they often start from scratch. We’re building so much, but the truth is—even though we are taking space, participating in important conversations, offering services, and creating art, most are unaware or don't have access to this.

NIKKI: Allan makes a great point about stability because, within art, we need to obtain the privilege to do artistic works and to have the freedom to break out of that mentality of just trying to survive.

DRE: I feel that there are not enough leaders out there. We need role models that push that ideology.

NIKKI: What’s holding us back?

DRE: The way we’re exposed to that Filipino crab mentality. I think with the current generation, they’re more open to deleting it.

ALLAN: The thing is—and this relates to our community work—work like this never ends. Because of how our migration channels work, we’re always going to need to help new families. So, [there are a lot of different] motivations and obligations. People come here for a better life, but that doesn’t necessarily relate to art. Art is a tertiary thought.

KHRYSTA: When you’re busy surviving, do you really have time to [pause and] reflect? Time is precious. And with capitalism, time is money. And the less money you have, the less time you have to think.

ALLAN: It takes maybe a generation or two to be able to have the curiosity to at least consume art or be exposed to it. So when it comes to the future of the Filipino, I’d love to imagine someone who is radical and influenced by many past artists. But the truth is, how possible is that?

You need to have a sort of entitlement to access that mindset.

NIKKI: A lot of migrants have working or below-working-class backgrounds. For example, when my mom came here, she was at the bottom of the food chain in the Philippines. There’s this sort of dynamic at play in terms of poverty, where there will always be someone poorer than you. When did she ever have the opportunity to think about art—when she was trying to live and simultaneously send that money to the Philippines?

ALLAN: But even then, even if you could live comfortably, who says that you’re going to jump into art, right?

NIKKI: Exactly. Dre, for non-Filipino readers, what’s the crab mentality?

DRE: It’s when one Filipino thinks they’re better than other Filipinos. It’s a competitive cycle where we can get the approval of [other people in the community]. It comes from how older generations grew up, where everyone was on their own. They could only support their immediate family.

NIKKI: When you look at other communities, they don’t really have that.

DRE: Yeah, they take pride in supporting their community members—promoting their businesses and each other.

NIKKI: So what does stability mean for you?

DRE: It’s to have our presence more known. Recently, people are starting to understand that we’re not just a generalization but a specific Asian [with our unique history].

KHRYSTA: This question has so many layers. That's why it's so hard to crack and that's why it's so difficult as well to solve.

NIKKI: When it comes to looking at the future, it’s about embracing your past. What comes to mind?

DRE: It’s about being older and wiser. Now I can look back on my experiences and that if I knew the stuff I do now, things could have been better or progressed faster. You see that now with how we’re teaching the youth by sharing what we’ve learned.

NIKKI: It’s interesting because not many of us know that we’ve been in North America for centuries, going way back to the 1600s! And it’s a shame that we’ve been here so long, but we don’t have the same cultural foundation as the Chinese communities. Maybe that comes down to the crab mentality. Maybe that comes down to other things.

KHRYSTA: You know what we have? Survival skills. In Physical 100, there’s a rock climber that’s really skilled because he saves lives. He’s got real muscles from saving people and surviving. With Filipinos, we’re the same. We’ve got thick skin [from having to survive], from having to learn the language to understand how to live. And it’s such a common story that we have films and TV shows about our migration patterns.

I feel like the future of the Philippines is very similar to how we live right now. Even just ten years ago with how we’ve adapted to different presidents with different intentions. Adaptability—how we can immediately react to situations—is our strongest asset, where we can build things out of nothing.

NIKKI: We’re scrappers. But how do we go beyond just trying to survive?

KHRYSTA: I feel like we shouldn’t solely give in to the [stereotype] that Filipinos are hard workers. We think that by working more, we’ll get a bigger reward from working that much harder. Different colonizers sold us their dreams, and today Filipinos go abroad to chase the American dream—but once you get there, it’s an unforgiving place. There’s a movie about that called Perfumed Nightmare (1977).

NIKKI: We give our bodies away.

KHRYSTA: That’s the thing I can’t stop thinking about. The only way [to have a future] is to look back at where we came from and analyze what the fuck went wrong. Now, people are learning how that’s influenced by all the people who’ve invaded and colonized us. With stability, I’m [thinking] about it in a way that’s more than [just practicality or financial stability]. It’s the attitude.

NIKKI: So how do we communicate that?

KHRYSTA: I’m trying to incorporate [these ideas] with my art. When I used to paint, I was painting about [my experience living in] the Philippines. I’d talk to other Filipinos in art school, and they’d [say the same thing]. Like, what does that mean?

ALLAN: A lot of what I do is related to my identity. Specifically, that means reconnecting to our traditions and mythologies because they influence our mannerisms and culture. But it’s also important to look at what more modern artists have been doing and see what messages they shared 10 or 20 years ago. But you need to have the skills to do research. Early in my practice, I was trying to learn about Filipinos in Montreal. Obviously, I Googled it. [At that time], the results weren’t great. But, what surprised me was going into university libraries and reading academic papers from Filipino graduates that focused on the community. I mean, that, too, comes with having the privilege of getting into higher education.

KHRYSTA: You know, it’s like the idea of being Filipino and making art about our country versus being Filipino and making art in general. It’s something so deeply ingrained in us. For me, I’ve got to pour my heart and soul into a claymation short film to tell people about our realities.

NIKKI: Dre, in terms of food, how does that look?

DRE: I’ve always wanted to introduce Filipino food to the masses. Before, I thought the way to do it was through fusion cuisine and turning Filipino food into more Westernized dishes. But, as I got older, especially with today’s palates and food diversity, there’s more [room for authenticity].

Now, I’ve learned more to appreciate the cooking of my past. The food from my mother and my grandmothers. From my dad’s cooking, too. Now, my food is more “nostalgic cooking,” more true-to-heart—making you reminisce about the past.

NIKKI: It all starts with intention. We need to be stable enough to find the kind of initiative—the courage—to get past that and create these role models that will inspire these new expressions.

KHRYSTA: Newer generations have a better possibility of making change.

DRE: Definitely. Our food has a story to tell. And we need those storytellers to tell our stories.

KHRYSTA: Whether it's from your dream, or nightmare, or reality, if you want it, you can just tell a story. The hardest part of storytelling is uncovering our roots and finding something that inspires you.

ALLAN: [It comes down to us, too]. At a young age, we’ve been taught generations ago that we’re not good enough the way we are. We need to work on addressing and healing intergenerational trauma so that the youth can dream of whatever future they want.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nikki Celis is a Bicolano writer and multimedia creator based in Montreal, Canada. He loves a good Bicolano swear word and is an avid spice fiend. When he’s not writing, you’ll find him studying techniques from muay thai legends from the golden age. @sapatos.docx

Nikki Celis is a Bicolano writer and multimedia creator based in Montreal, Canada. He loves a good Bicolano swear word and is an avid spice fiend. When he’s not writing, you’ll find him studying techniques from muay thai legends from the golden age. @sapatos.docx

ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR

Following studies in graphic design and visual arts, Elie started illustrating as a way to better understand himself. Elie tends to concentrate his imagery between his life and over the top imagination. He believes that through his art, people will better understand him. Elie also started his own print studio, freelances and works full time in the fashion industry.

Following studies in graphic design and visual arts, Elie started illustrating as a way to better understand himself. Elie tends to concentrate his imagery between his life and over the top imagination. He believes that through his art, people will better understand him. Elie also started his own print studio, freelances and works full time in the fashion industry.