SPAM

Words by Nikki Celis

Illustrations by Sean C. Kershaw

April 28th, 2021

Illustrations by Sean C. Kershaw

April 28th, 2021

Lately, I’ve been dreaming of SPAM.

No, not the unsolicited emails that one receives daily in their inbox. But rather, the canned meat so often associated with lowbrow culture.

Cue scene. I’m standing in the centre of the main aisle of a supermarket with a black plastic basket. The overall milieu of the grocer is familiar. Old light fixtures glare at you like you’re not supposed to be there. The smell of fresh produce contrasts with the acrid, peculiar smell of fresh and frozen seafood. The tinny sound of top 40 hits blast through old speakers.

I notice the off-white, mostly yellow tiled floor, recently coated to prevent wear. The sequential aisles are devoid of human contact, as evidenced by untouched shelves so often tampered by reckless hands. I can hear the speakers blare “Royals” by Lorde as I make my way to the canned and packaged goods section, the products undefinable and unappealing. I make a left, and then another.

In front of me is an entire section dedicated to SPAM. Stacked in the dozens. The details of each can impeccably definable: the brass rims, the blue wrapper, the yellow logo—and of course, a pink, glistening slice of SPAM sandwiched in between American-style cheese, lettuce, tomato, onion, mustard, and white sesame bread.

For the next few nights, the dreams play out the same. Like a sequence in a production line. Each night I would make my way to the shelf of SPAM, grab a can of regular and premium and then wake up, chuckling to myself.

###

Out of all things, why SPAM?When I brought it up with friends, they laughed. But I genuinely wondered why. A few weeks later, I discovered the work of the late Doreen G. Fernandez, a renowned Filipino food historian, critic, and educator.

Her works were seminal in providing remarkable insight and appreciation towards Filipino cuisine and how it ties with culture—something I regarded with disdain, not unlike my peers here in Canada and in the Philippines.

The process of eating, Fernandez continues, is not only the consumption of the environment but also the ingestion of culture.”

Food is directly tied to one’s heritage. A common knowledge. The Philippines itself is in a peculiar position, with centuries of colonial influence brought upon by the initial occupation of Spain, United States, and Japan. And this doesn’t exclude the epicurean influence brought in by French-influenced Filipinos in the early 1900’s (“Beyond Sans Rival: Exploring the French Influence on Philippine Gastronomy”), nor the pre-colonial culinary influence of India and China.

As a second-generation Filipo-Canadian, I’ve always felt removed from my own community.

A natural feeling. Having been strongly affected by systemic white racial framing—for as long as I can remember—navigating between that of my own ethnic identity and the one imposed by the dominant culture has placed me in a perpetual state of in-betweenness.

Coupled with the community’s enthusiasm to be part of the prevailing culture, it’s an often-said idea that my culture is one of bastardization. And if that’s the case, how do you connect with your own heritage when it’s trying so hard to be something it’s not?

Did you know that papaya soap actually makes you whiter? In fact, there’s an entire industry in the Philippines dedicated to skin whitening—though, when all else fails, there’s laundry detergent.

And if it isn’t the skin, it’s the encouragement that many youths receive from their parents, telling them to only speak English (opportunities open when you can speak English more fluently than your white friends).

This is compounded further by cultural conditioning prevalent in Philippine media—where Korean celebrities and mestiza actors speak in taglish in the most banal television sitcoms or teleseryas. Or in the movies where, if it isn’t poverty porn, it’s the embellishing of the elite or middle-class. In most cases, we are fostered into an environment where we have to be as white as we can be.

An impossible standard.

What’s ignored, however, is what Fernandez calls—listen—a process of “borrowing.”

In her exploration of cuisine, through her 1988 essay “Culture Ingested: Notes on the Indigenization of Philippine Food,” she remarks: “The reason for the confusion is that Philippine cuisine, as dynamic as any phase of culture that is alive and growing, has changed through history, absorbing influences, indigenizing, adjusting to new technology and tastes and thus evolving.”

The process of eating, Fernandez continues, is not only the consumption of the environment but also the ingestion of culture: “since among the most visible, most discernible and most permanent traces left by foreign cultures on Philippine life is food that is now part of the everyday, and often not recognized as foreign, so thoroughly has it been absorbed into the native lifestyle.”

And yet, among this mishmash of culinary fusion—out of the array of Chinese-influenced foods (lugaw/congee), Spanish (adobo/adobado), Japanese (halo-halo/ kakigōri), and even the indigenous cuisine still cooked at home—the most striking, poignant memory to ever pervade my dreams is an American lowbrow product that doesn’t even require any preparation.

###As a second-generation Filipo-Canadian, I’ve always felt removed from my own community.

A natural feeling. Having been strongly affected by systemic white racial framing—for as long as I can remember—navigating between that of my own ethnic identity and the one imposed by the dominant culture has placed me in a perpetual state of in-betweenness.

Coupled with the community’s enthusiasm to be part of the prevailing culture, it’s an often-said idea that my culture is one of bastardization. And if that’s the case, how do you connect with your own heritage when it’s trying so hard to be something it’s not?

Did you know that papaya soap actually makes you whiter? In fact, there’s an entire industry in the Philippines dedicated to skin whitening—though, when all else fails, there’s laundry detergent.

And if it isn’t the skin, it’s the encouragement that many youths receive from their parents, telling them to only speak English (opportunities open when you can speak English more fluently than your white friends).

This is compounded further by cultural conditioning prevalent in Philippine media—where Korean celebrities and mestiza actors speak in taglish in the most banal television sitcoms or teleseryas. Or in the movies where, if it isn’t poverty porn, it’s the embellishing of the elite or middle-class. In most cases, we are fostered into an environment where we have to be as white as we can be.

An impossible standard.

What’s ignored, however, is what Fernandez calls—listen—a process of “borrowing.”

In her exploration of cuisine, through her 1988 essay “Culture Ingested: Notes on the Indigenization of Philippine Food,” she remarks: “The reason for the confusion is that Philippine cuisine, as dynamic as any phase of culture that is alive and growing, has changed through history, absorbing influences, indigenizing, adjusting to new technology and tastes and thus evolving.”

The process of eating, Fernandez continues, is not only the consumption of the environment but also the ingestion of culture: “since among the most visible, most discernible and most permanent traces left by foreign cultures on Philippine life is food that is now part of the everyday, and often not recognized as foreign, so thoroughly has it been absorbed into the native lifestyle.”

And yet, among this mishmash of culinary fusion—out of the array of Chinese-influenced foods (lugaw/congee), Spanish (adobo/adobado), Japanese (halo-halo/ kakigōri), and even the indigenous cuisine still cooked at home—the most striking, poignant memory to ever pervade my dreams is an American lowbrow product that doesn’t even require any preparation.

“...in some ways, food is home.”

What’s so romantic about SPAM?

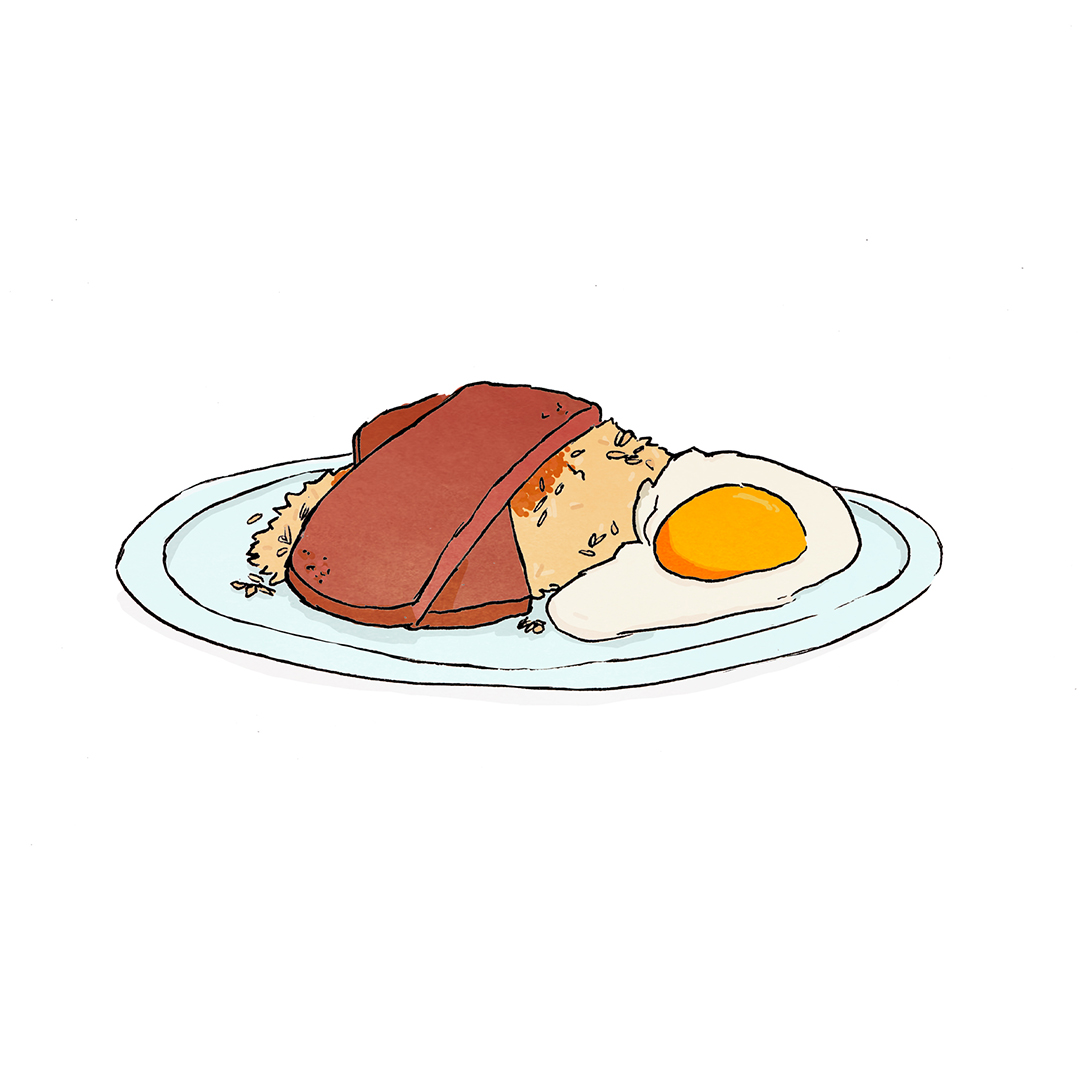

From what I can recall of my childhood—small, vague memories that are hard to piece together—I can distinctly remember the heavy, dense, salt-infused musk of SPAM as it’s left to fry in its own gelatinous mystery-liquid. In the pan, too, are eggs, fried on both sides until the whites are non-existent.

We’re in one of my childhood homes in Abbeydale, Calgary. My mother is young in this memory. Only traces of white hair can be seen among the black, curly strands on her head.

She’s in this minuscule kitchen by this equally small, muddled-yellow stove tending to the cooking while sweet Filipino (also Hawaiian) dinner rolls—pandesal—are left to toast in the oven. Dad is only home in the evenings—an electrician at the time, though he often dabbled in other things away from the privy of mom.

Each slice sizzles until both sides are red and crisp. The eggs, cooked thoroughly, show no signs of leakage. With a fork, mom places a slice of SPAM and a fried egg in an open-faced pandesal, toasted and browned, and then moves it onto a large plate. I’m salivating, withholding my intense desire to grab them with my tiny sausage fingers and eat the whole plate surreptitiously.

“Ka-in na,” she says, smiling. “Let’s eat.” And I do so willingly.

When we have SPAM or canned food—my mother still (albeit sparingly), stocks her pantry with products such as corned beef, Vienna sausages, sardines and the like. We bear no prejudices of how these items tie with class and socioeconomic status. Food is food.

And in some ways, food is home.

From what I can recall of my childhood—small, vague memories that are hard to piece together—I can distinctly remember the heavy, dense, salt-infused musk of SPAM as it’s left to fry in its own gelatinous mystery-liquid. In the pan, too, are eggs, fried on both sides until the whites are non-existent.

We’re in one of my childhood homes in Abbeydale, Calgary. My mother is young in this memory. Only traces of white hair can be seen among the black, curly strands on her head.

She’s in this minuscule kitchen by this equally small, muddled-yellow stove tending to the cooking while sweet Filipino (also Hawaiian) dinner rolls—pandesal—are left to toast in the oven. Dad is only home in the evenings—an electrician at the time, though he often dabbled in other things away from the privy of mom.

Each slice sizzles until both sides are red and crisp. The eggs, cooked thoroughly, show no signs of leakage. With a fork, mom places a slice of SPAM and a fried egg in an open-faced pandesal, toasted and browned, and then moves it onto a large plate. I’m salivating, withholding my intense desire to grab them with my tiny sausage fingers and eat the whole plate surreptitiously.

“Ka-in na,” she says, smiling. “Let’s eat.” And I do so willingly.

When we have SPAM or canned food—my mother still (albeit sparingly), stocks her pantry with products such as corned beef, Vienna sausages, sardines and the like. We bear no prejudices of how these items tie with class and socioeconomic status. Food is food.

And in some ways, food is home.

Released to the public in 1937, the kitsch, often maligned pork shoulder preserve known with a refrained acceptance among American housewives hadn’t attained its global prominence until WWII.

A portmanteau for “spice” and “ham,” its ability to retain edibility despite being exposed to extreme temperature became a mainstay for American GIs.

Though, despite its availability, it never garnered any particular praise. Jay Hormel, son of corporation founder George Hormel, and head of the company from 1929-1954, for example, received a myriad of hate mail, which he calls the “Scurrilous File.”

From 1942-1945, Japanese forces briefly occupied the Philippines, threatening decades of American occupation (1898-1946) that “liberated” the country from 333 years of Spanish colonialism.

Subsequently, the United States declared war against Japan after the events of Pearl Harbor, with American and Filipino forces fighting against the Japanese as part of an overall assault throughout the Pacific theatre. Though the Japanese Empire officially surrendered in 1945 and relinquished the Philippines from their control, an estimated one million Filipinos died, with many villages, towns, and cities—notably Manila—reduced to shambles.

With a lack of stable infrastructure, and many Filipinos displaced after the war, as well as many Americans establishing permanent residency within the country either as civilians or as military personnel, the rations that kept Americans relatively well-fed in comparison to other Allied forces—namely, SPAM—had likely then become a staple in the limited Filipino diet, further exacerbated due to a lack of traditional food sources.

Within the same period, American intervention against the Japanese also introduced other cultures throughout the pacific theatre to various Americanisms shared among locals.

“Beer, chewing gum, military rations—including tinned meats such as SPAM—became valuable artifacts of the most recent occupying culture and as such prized by locals,” writes George H. Lewis in his essay “From Minnesota Fat to Seoul Food: SPAM in America and the Pacific Rim (2000).”

Fast forward to today and SPAM remains ever popular outside of the Occident. Hawaii (the largest consumer), Korea, Japan and, of course, the Philippines, have this American product tied so intrinsically to their cultural (and culinary) identity.

Rather than eating the pre-cooked meat from the can as-is, the product is a borrowed and thus indigenized ingredient for many popular dishes: SPAM musubi, an onigiri-like dish from Hawaii; budae-jjigae (Army Base Stew), a noodle-dish paired with a smorgasbord of food items cooked in a Kimchi stew in Korea; as well as fried or steamed rice paired with SPAM and eggs, which may or may not be seen as a common unifying dish among many cultures throughout Asia and the Pacific.

The pairing of SPAM and rice, or SPAM sandwiched in between pandesal, though a relatively simple dish to prepare, is also an anchor to much of what I can remember of my youth.

In supermarkets across the Philippines, there are aisles purely dedicated to the product. Other luncheon meats, local variations and those imported from neighbouring countries such as Ma Ling sell for considerably less than the real American deal.

One 12oz can of SPAM sells for an average of P135, slightly more than a quarter of Manila’s daily minimum wage, P491, averaging at about $13 CAD (2017).

And yet, millions of pounds of SPAM are consumed yearly (a significant detriment to the Filipino diet). Such a preference over localized varieties of what is essentially the same product shows how Filipino culture holds Western values, ideas, and products to the highest esteem.

A portmanteau for “spice” and “ham,” its ability to retain edibility despite being exposed to extreme temperature became a mainstay for American GIs.

Though, despite its availability, it never garnered any particular praise. Jay Hormel, son of corporation founder George Hormel, and head of the company from 1929-1954, for example, received a myriad of hate mail, which he calls the “Scurrilous File.”

From 1942-1945, Japanese forces briefly occupied the Philippines, threatening decades of American occupation (1898-1946) that “liberated” the country from 333 years of Spanish colonialism.

Subsequently, the United States declared war against Japan after the events of Pearl Harbor, with American and Filipino forces fighting against the Japanese as part of an overall assault throughout the Pacific theatre. Though the Japanese Empire officially surrendered in 1945 and relinquished the Philippines from their control, an estimated one million Filipinos died, with many villages, towns, and cities—notably Manila—reduced to shambles.

With a lack of stable infrastructure, and many Filipinos displaced after the war, as well as many Americans establishing permanent residency within the country either as civilians or as military personnel, the rations that kept Americans relatively well-fed in comparison to other Allied forces—namely, SPAM—had likely then become a staple in the limited Filipino diet, further exacerbated due to a lack of traditional food sources.

Within the same period, American intervention against the Japanese also introduced other cultures throughout the pacific theatre to various Americanisms shared among locals.

“Beer, chewing gum, military rations—including tinned meats such as SPAM—became valuable artifacts of the most recent occupying culture and as such prized by locals,” writes George H. Lewis in his essay “From Minnesota Fat to Seoul Food: SPAM in America and the Pacific Rim (2000).”

Fast forward to today and SPAM remains ever popular outside of the Occident. Hawaii (the largest consumer), Korea, Japan and, of course, the Philippines, have this American product tied so intrinsically to their cultural (and culinary) identity.

Rather than eating the pre-cooked meat from the can as-is, the product is a borrowed and thus indigenized ingredient for many popular dishes: SPAM musubi, an onigiri-like dish from Hawaii; budae-jjigae (Army Base Stew), a noodle-dish paired with a smorgasbord of food items cooked in a Kimchi stew in Korea; as well as fried or steamed rice paired with SPAM and eggs, which may or may not be seen as a common unifying dish among many cultures throughout Asia and the Pacific.

The pairing of SPAM and rice, or SPAM sandwiched in between pandesal, though a relatively simple dish to prepare, is also an anchor to much of what I can remember of my youth.

In supermarkets across the Philippines, there are aisles purely dedicated to the product. Other luncheon meats, local variations and those imported from neighbouring countries such as Ma Ling sell for considerably less than the real American deal.

One 12oz can of SPAM sells for an average of P135, slightly more than a quarter of Manila’s daily minimum wage, P491, averaging at about $13 CAD (2017).

And yet, millions of pounds of SPAM are consumed yearly (a significant detriment to the Filipino diet). Such a preference over localized varieties of what is essentially the same product shows how Filipino culture holds Western values, ideas, and products to the highest esteem.

While Fernandez writes in “Mass Culture and Cultural Policy: The Philippine Experience” (1989) that centuries of Spanish colonization had introduced the very fabric of Filipino identity, from “religion, law, town-planning . . . exterior and interior architecture, food, music, dance, drama, words incorporated into native languages, social customs, systems of patronage and ritual kinship, but also a certain Latin bravura,” the subsequent American occupation, though short, had instilled a more profound effect to the Filipino character through our conditioned aspirations for whiteness.

Its influence was everywhere: from the education system “which brought attitudes, values, concepts, aspirations;” the esteem of social class tied to one’s command of the English language; contemporary politics, much of it adhering to American political philosophy.

The biggest culprit, though? Popular culture (more evident than ever before) disseminated through the increased accessibility of television, movies, and—obviously—the internet. All of these echo the apple pie ideal. It screams America, in a Twilight Zone sort of way. Like a foster child living among a family of many, neglected and yearning for recognition.

###

I’m left wondering.

With all these implications, does it really impact how I perceive my own culture?

When my mother first immigrated to Calgary in the 80’s, did she come wanting to be a part of this American/Canadian ideal? When she met my father, married him and gave birth to me alone in a hospital room in Rockyview—carrying the burden of dysfunction so tied with my familial upbringing—did she dream that I would seamlessly integrate into society and become a perfect, model Canadian?

God, I hope not.

A part of me feels like I’m the very product that I’m obsessing over: an amalgamation of meats, preservatives and god-knows-what-else wrapped and presented in a tin, shelved with many others shouting at the world, “eat me, I’m palatable!”

So servile are we—am I—to the Western ideologue. Always wanting to please. Always wanting to belong and yet never truly attaining it. Not even within the broad, general category of being “Asian” (my Asianness was questioned for traditionally eating with a spoon and fork instead of chopsticks).

Like SPAM, even as an ingredient or a singular element among a wide range of qualities, it is seen as the Other.

And while it has a place among the poor, the working class, the immigrants and the children born of them, it is still patronized by those who—subconsciously—perceive themselves as greater and ultimately incorporated into society with a refrained acceptance.

If this is the foundational element that ties me to my very own ethnic identity, then am I simply a byproduct of post-colonial influences?

And if I’m not palatable enough—beyond the service industry in which we dominate—if I took it upon myself to sizzle in a frying pan to bring out the umami and nestle myself with garnishing just so I’m presentable enough for you to have a morsel, would you like me more?

Would I like myself more?

What I can say with absolute certainty is that, ultimately, if I were to ignore the research and the revelations, then this is my reminder of home. Uncanny, to be euphemistic.

Not of the Philippines, nor of Canada, but of the tiny kitchen in Abbeydale where my mother cooked breakfast ignorant of a product’s implied—and depressing—history. Where I can see her smile as I salivate with my Vienna sausage stump fingers, clawing for a slice of crisp, pink meat and an overdone egg, sandwiched in between toasted pandesal.

At least, on the surface, this memory provides context to my SPAM dreams. And with that dream comes fantasy, or at least an ideal that I can never re-experience. Only revisit.

It is a moment in which I can revel in its authenticity—if not for a second—until I find myself in a world where I am constantly lost, despite my own embellishments. Where I’m naked and served on a platter for the whole world to see—and to determine my own authenticity (am I “good to think” or “bad to think”? Am I American/Canadian enough?). My skin removed, flesh laid bare, where I constantly scream for someone to have a bite. Where one day I can hear someone say, “hmm, that’s not so bad,” admire me—if not for a second—before throwing me into the trash.

And yet, revisiting this piece three years later in 2021, it is still nothing but a fantasy.

Today, we are hyper-examined, constantly needing to prove our Westernness, where an American veteran and elected official Lee Wong—regardless of his partisanship—has to physically show his scars to prove his authenticity and his place within the hegemony.

It is nothing but frustrating. Yet it is still very much par for the course.

But what I can say is this: the idea of being Asian and Pacific Islander lies in the strength of its amalgamated identities. You and I, despite our inherited differences, came together in solidarity to navigate through the experience of Otherness. And we can do it again—because we are more than enough.

It’s all just in the manner of presentation.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nikki Celis is a writer and multimedia creator based in Montreal, QC. His work has been published in Noisey, The Calgary Herald, The Georgia Straight and more. On the side, Nikki is part of the shoegaze duo cmfrtble. and likes to enjoy a good melona bar.

Nikki Celis is a writer and multimedia creator based in Montreal, QC. His work has been published in Noisey, The Calgary Herald, The Georgia Straight and more. On the side, Nikki is part of the shoegaze duo cmfrtble. and likes to enjoy a good melona bar.